In an earlier post, I attempted to define liberalism, and ended up concluding that it essentially comes down to supporting “government of the people, by the people, and for the people.” Or to put it more specifically, liberalism can be defined as a political movement that seeks to improve our social institutions so they become more beneficial, according to the needs and desires of the general populace. But I’ve never clarified conservatism in the same way, and I think I can now do so. One obstacle that kept me from arriving at such clarity is that conservatism is not a single unified thing — it is, I now believe, two separate things which work in tandem toward a common goal. One of these drives the majority of grassroots supporters of conservatism, and the other drives those who use it to gain power.

(more…)October 1, 2023

September 15, 2022

search engines used to be dumb, but now they’re stupid

What is the difference between dumb and stupid? I’m using the word “dumb” here in a specific sense, as a jargon term which is common among engineers and coders. A “dumb” device is one which does one simple thing and does not try to do more, while a “smart” one is encumbered with automated features and add-ons. A smart phone, for instance, tries to do as many things as possible, whereas a dumb phone only makes telephone calls. A smart microwave is able to automate tasks like defrosting meat and popping popcorn; to enable this it has 27 buttons, half of which are useless without repeated study of the manual. A dumb microwave, on the other hand, can be operated by anyone the first time they see it, because all they need to do is turn one knob.

Sometimes smart is good, and other times dumb is actually the better option. I want my phone to be smart but my microwave to be dumb. Hand tools such as crowbars and can openers are dumb, and that is a virtue. Smart devices are usually faddish, temperamental, and rapidly obsoleted; dumb ones may still be valuable or coveted a hundred years later.

Dumbness is relative. Back in the days of timeshare computing, for instance, it was common to access systems remotely with a device that combined a video display and a keyboard, which was called a terminal. As microcomputers started to appear these quickly came to be called “dumb terminals” because they did not contain their own computers. This just adopted the usage of an existing term, as the phrase had already been applied to basic terminals which lacked fancier features. Despite being called dumb, these devices were quite complex, and would be considered smart if compared to, say, a typical television set of the time. Similarly, the dumbest telephones commonly in use today — the wireless handsets favored by those who still use landlines — would be considered smart in comparison to a traditional rotary-dial phone.

(more…)June 20, 2022

the meanings of “meaning”

I recently watched a video by Kyle Kallgren where he talks about Umberto Eco, which means talking about semiotics, which is the philosophical study of signs, symbols, and meaning. And while I definitely enjoy and appreciate Kallgren’s work, there’s a side to the meaning of meaning that he didn’t really mention or go into. I’m not sure if the big name semioticists he talked about really did either. And the aspect of meaning that I think got missed has to do with the kind of meaning that Douglas Hofstadter talked about back in the seventies in Gödel, Escher, Bach: meaning that inherently emerges because the signifier has an isomorphic relationship to that which is signified, like the way a road map relates to actual roads. The map conveys true messages about how the roads connect, and that meaning can be decoded even by someone who’s never seen a map before, once they observe enough of the roads to notice the matching patterns.

(more…)April 23, 2022

Bitcoin is a Ponzi scheme

Cryptocurrencies were supposed to be a new tool of commerce for people who don’t trust governments, not an investment commodity or a get-rich-quick scheme. Yet that’s what they’ve turned into. And the further we get into it, the harder it is to see the whole idea as anything but a con.

(more…)February 27, 2022

The Investigation of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Theory of the Bicameral Mind

I’m rereading the book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind by Julian Jaynes. This is the kind of book that gets called seminal, because it is bursting with original thoughts and ideas and insights that can be quite inspiring to many readers. It is also the kind of book that gets called pseudoscientific crackpottery, because it’s also bursting with extravagant semi-untestable assertions based on thin evidence. I think many who’ve read it can relate to Richard Dawkins when he called it “either complete rubbish or a work of consummate genius; nothing in between”, and even some of its defenders will nod their heads at statements like “On first reading, [it] seemed one of the craziest books ever written” (Gregory Cochran). In modern terms, the book is usually described as “discredited”.

But despite the fact that I don’t think its controversial core theory is true, I still see a lot to value in the book, and recommend it as a thought-provoker. And one reason for this is because a lot of us still carry around a lot of naive ideas about conscious self-awareness that Jaynes does a good job of challenging, just by bringing an unusually clear eye to everyday acts of introspection.

(more…)November 9, 2021

the right wing’s rejection of reality is now its defining attribute

In earlier times, if we wanted to explain the difference between the left and the right in politics, we might talk about individual vs community, or big vs small government, or diplomacy vs militarism, or multiculturalism vs traditionalism, or equality vs inequality, or even communism vs capitalism. You could say it divides people between the compassionate and the selfish, or between the religious and the secular, or even just between the urban and the rural. But nowadays, in the United States of America, all such historical distinctions have now become secondary. What now separates our left and right is that one holds to reality while the other wholeheartedly rejects objective reality for fantasies and lies. One is sane and the other is not.

Some see this disconnection from objective reality as a sudden and startling transformation, but if you’ve been paying attention, it isn’t. Our right wing has been building up to this for a long time.

(more…)October 30, 2021

the novel “Dune” is both great and flawed

Dune, the career-defining 1965 novel by Frank Herbert which is the source of the current blockbuster film, is certainly a magnificent epic. It is a richly complex work with a lot of meaning, and it deconstructs a lot of narrative tropes familiar from our favorite legends and entertainment, at a time when such things were usually accepted uncritically. Hero’s journey, chosen one, white savior — they’re all there, played halfway straight but always askew and always illuminated from an unusual angle that makes you see it in a new way. And the book is packed with everything that was popular and trendy in its time, from martial arts to mind-expanding drugs, from youth rebellion to superpower origin stories, from the feudal struggles of high fantasy to the new science of ecology.

(Someone recently summarized the tale, when asked to boil it down to one sentence, as a bunch of greedy horny men failing to peacefully share a planet made of cocaine.)

(more…)September 27, 2021

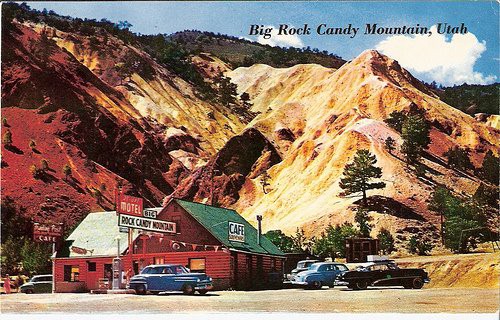

the strange road to the Big Rock Candy Mountain

Some years ago, I looked out of an airplane into the southwestern desert and saw a remarkable sight: a mountain banded with an variety of rich colors. I pulled out my phone and managed to get a GPS fix, and was able to look up the location later. It turned out that what I had seen was the Big Rock Candy Mountain, which I had always assumed was an imaginary place.

So I had to look up whether the song had been named after the mountain or the mountain had been named after the song. It was apparently the latter: when the song became popular the residents near the mountain put up signs claiming the name for this volcanic hill, and also a sign proclaiming Lemonade Springs. But on the other hand, some say that railroad men had been using the name a lot earlier. And in learning what the mountain was called, I also learned something about the history of the song itself, which is a lot stranger than you’d think.

(more…)July 17, 2021

civilization is exploitation?

In certain circles, it is not difficult to hear someone pronounce the phrase “Capitalism is exploitation.” Is this valid? I’m not gonna answer yes or no to that fraught question, as neither is entirely valid. What I am going to do is question the unstated implication that capitalism is somehow distinct in its exploitativity — the suggestion that since we’re equating exploitation to capitalism, this must mean that lots of other -isms are non-exploitative. If you put capitalism up against all the other organizing systems it has competed with, such as monarchy and theocracy and feudalism and colonialism and warlordism and all the rest… well, it’s less exploitative than most.

The history of civilization mostly consists of an endless succession of different kinds of emperors, god-kings, priesthoods, titled nobilities, conquering hordes, colonial occupiers, and other groups which use some combination of social control and brute violence to put themselves in a privileged position above other people, where they get to keep the lion’s share of whatever they want. And what they usually want in the largest quantity is labor. Ever since the human race started to urbanize, the fabric of every kind of society that we call civilized has usually consisted of a set of rules which define one group of people which serve and another which are served. In every land and in every age, self-appointed lords have declared themselves entitled to direct the labor of the masses, often for the benefit of their own class or their own family. And fighting and dying for their rulers in warfare was just one more form of this labor.

(more…)July 15, 2021

a comparison guide to asshole space billionaires

Elon Musk (SpaceX):

- wealth comes from overvalued Tesla stock that he can’t sell without crashing the price, so it’s mostly illusory

- forced the entire car industry to start shifting to electric motors, so he has probably done more than any other person to reduce global warming

- approaches all problems by thinking first of basic physics, then engineering, then manufacturing at scale, then financial stuff last

- the only private space entrepreneur to successfully sell satellite launches in quantity and make a profit at it

- reusing boosters forced the other rocket builders to scramble just as hard as the auto companies

- in that scramble, the ones who suffered the worst losses were the Russians

- will soon send tourists on a multiday orbital flight, which makes the brief suborbital hops offered by the next two look pretty feeble

- is now filling the sky with thousands of internet satellites which will make life tough for astronomers and might trigger a catastrophic space junk crisis (google “Kessler syndrome”)

- wants to move a million people permanently to Mars

- had a child with pop star and art dilettante Grimes; naming the kid “X Æ A-12” was apparently her idea

- can’t keep his mouth shut when ordered by the SEC to stop tweeting things that influence stock prices

- other mouthing off has gotten him in legal trouble… and he’s in court right now, arguing that it’s good for the company because being “entertaining” saves advertising costs

- denied the severity of covid and tried to force all his workers to stay in factories at the height of the pandemic

- generally overworks employees, and responds with threats if they mention unionizing

- abusive tirades have been reported

- has a hiring philosophy of “no assholes”, but is one

Jeff Bezos (Blue Origin):

- wealth comes from paying people the lowest possible wages for the hardest possible warehouse labor, with intentionally high rates of burnout and turnover

- Amazon makes very little profit, so all the money it makes somehow ends up owned by Bezos rather than the company

- said to be intensely envious of Musk, trying to equal his accomplishments without realizing that you’d have to equal his brains first

- a Trump-aligned tabloid once tried to blackmail him over infidelity, and found out that Jeff don’t blackmail

- but what they found may have brought about the biggest divorce property division of all time

- spent billions and billions on space for twenty years without launching a single thing for a paying customer

- sold United Launch Alliance (the Pentagon’s favorite rocket builder) on a new engine for their forthcoming Vulcan rocket, and is now failing to deliver the engine, forcing the Vulcan to be delayed

- also wants to fill the sky with thousands of internet satellites, but will probably fail to compete with SpaceX’s version, thereby rendering the satellite swarm useless as well as obtrusive

- wants to move a million people to Earth orbit, along with heavy industry to relieve the environment down here

- suckered some schmuck into bidding $26 million to sit next to him on the first brief tourist flight of the New Shepard

- is a way bigger asshole than Musk… or at least he used to be

Richard Branson (Virgin Galactic, Virgin Orbit):

- wealth comes from selling music, airline travel, railroads, hotels, gyms, clothing, advertising, cellphone service, motorbike taxis, books, business services… just about anything they could think of, all under one name

- but for some of those he just sells companies the right to use the Virgin name, like Trump does

- why just have one space company when you can have two?

- unlike Bezos, has actually delivered a satellite into orbit, and people to zero gee (though Bezos is days away from catching up on the latter)

- started accepting money for SpaceShipTwo tickets back in 2006, but the first flight with private passengers was not until 2021

- but on the other hand, was offered a billion dollar investment by the Saudis and turned it down over their human rights problems

- has no plans to move a million people anywhere

- was an “adventurer” before he ever dabbled in space… crossed the Pacific in a hot air balloon, etc

- his love life is apparently adventurous too, with at least one open marriage, and a tendency to inappropriate behavior when drinking

- likes recreational drugs and wants them legalized

- likes to come up with creative ways to cheat on taxes, even after once being jailed for it

- has gotten four people killed working on his rockets, and four more severely injured, in two separate incidents

- yeah, these things qualify him as an asshole

Max Polyakov? (Firefly Aerospace):

- I can’t verify for sure whether he qualifies as a billionaire

- wealth comes mainly from commercial real estate and e-commerce

- grew up in Ukraine, where his parents worked in aerospace, and where he has founded a new engineering school

- moved to Silicon Valley and then to Scotland

- was a co-owner of dating websites accused of being scams; for this reason, subject to distrust in the business world

- …on top of the distrust they already have for the idea of mixing American national security work with Ukrainian aerospace companies that may be influenced by gangsters

- Polyakov’s main goal other than profit is probably to revitalize high-tech industry in his homeland, which has suffered many setbacks

- Firefly was sued by Virgin Orbit and bankrupted by legal troubles; that’s when Polyakov bought it and revived it

- Firefly built their first completed rocket about eight months ago and delivered it to Vandenberg, but we’re still waiting for them to attempt to launch it

- Firefly’s only advantage in competing with Virgin Orbit or Rocket Lab is that they can (theoretically) lift somewhat heavier satellites, at a substantial cost increase

- much less public than the others, so I have no solid data on to what degree he’s an asshole

In summary, Musk is the most innovative, Bezos is the most despicable, Branson is the most reckless, and Polyakov is the most unimportant.

I haven’t mentioned the tendency to overpromise and exaggerate what their companies will do, because all new-space rocket company owners do that to roughly equal degrees, whether they’re billionaires or not.